‘Peter Nero: Classic Connections’ at Hylton Performing Arts Center

When I was about 11 years old, I saw the talented and comedic Victor Borge perform at the Academy of Music in Philadelphia. I wasn’t there to see him, though, I went to see Ann Jillian sing, and he performed with her. Now 25 years later, I don’t remember much about that performance, except being mesmerized by Borge’s skill at turning “Happy Birthday” (watch it below) into a classical and comedic masterpiece. I was hooked at how one song can be transformed into many different ways. In a sense, that performance influenced the type of musician I am today.

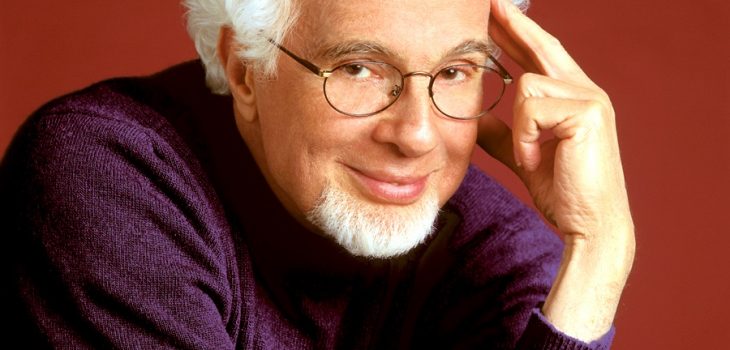

Peter Nero is a two-time Grammy Award-winning pianist and conductor, who just recently stepped down after 34 years as Music Director of the Philly Pops (who for almost 20 years performed in that same old opera house where Borge tickled the ivories that magical night). Nero has done it all: trained at Julliard; performed on Johnny Carson and Ed Sullivan; conducted orchestras all over the country; and has collaborated with such artists as Mel Torme and Doc Severinson. He is a truly unique musician -maybe one of the last of his kind – creating a bridge between classic music, pop music, and comedy.

Saturday’s night’s concert in the four-year-old Hylton Performing Arts Center on the Prince William campus of George Mason University was a complete evening of great music and entertainment. Nero plays the piano with such a jubilant intensity that he is a modern day Victor Borge. He plays classically as well as Arthur Rubinstein, rocks as masterfully as Elton John or Billy Joel, and entertains like a subdued Liberace.

Nero opened the concert with the classic Richard Rodgers song “Mountain Greenery,” accompanied by Mozart themes in his left hand. When Nero plays in his unique style, it is almost as if he is two people playing simultaneous patterns that are written to fit together perfectly. He went on to his ‘Andrew Lloyd Puccini’ section pointing out the obvious similarities between Phantom Of The Opera and La fanciulla del West. But he went one step further and bookended his mash-up with a bit of Maurice Ravel.

After a delightful rendition of Jerome Kern’s “All The Things You Are,” he played a beautiful Chopin piece with the melody of Stephen Sondheim’s “Send In The Clowns,” followed by an impression theme and variations on George Gershwin’s “I Got Rhythm,” as if they were written by Racmaninoff, Beethoven, Liszt, and Prokofiev.

The second half of his evening began with the famous Mozart tune, “Yellow Rose of Texas,” followed by an impressive improv jam session between himself and his equally as talented bassist, Michael Barnett. Barnett was playing an electric double bass, which almost seems like an oxymoron, but the tone of his instrument was very deep and wooden, and not at all metallic like normal electric basses produce.

Nero is also artfully comedic with his repartee with the audience and in one of many chats with the audience, he pointed out that due to an unfortunate missing line break in the program, the title of two Cole Porter songs became the new and very ironic song “Every Time We Say Goodbye It’s Alright With Me.”

The Hylton Performing Arts Center is a gorgeous new concert hall that is beautifully designed and has very crisp acoustics. On Saturday night for a brief moment I felt like I was back as my 11 year-old self at the Academy of Music, but only this time it was Peter Nero who left me mesmerized.

Running time: Two hours and fifteen minutes, with a twenty minute intermission.

Peter Nero: Classic Connections played September 21, 2013 at Hylton Performing Arts Center – 10960 George Mason Circle, in Manassas, VA. For future events, visit their calendar of upcoming events.

Posted on September 22, 2013 by Keith Tittermary