News

News

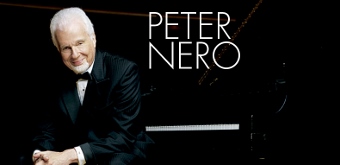

Fans hail the conquering Nero

The Philly Pops leader has thrived on his bond with the audience.

By Peter Dobrin

Inquirer Music Critic

The Philadelphia Enquirer

If the perfect pops conductor could be conjured, materializing on stage in a smartly proportioned package of art and entertainment, he might answer to this description:

Huge talent with polymath abilities and catholic tastes. Musician who actually enjoys giving audiences what they want. Maestro with charm to chat up donors and even carry on e-mail exchanges with fans. Plays piano like a dream.

If you crowned this conductor with a silvery aureole of hair and white goatee, then seasoned him with a musical trajectory that started on the New York children’s talent-show circuit and evolved into a big fat show-business career, he might look something like . . .

“Peter Nero! I just want to tell you how much I love your music,” says a young man stopping the conductor on Broad Street recently.

Nero smiles and shakes the man’s hand. “That’s why I decided to move here,” says the Philly Pops music director, who opens a stand of 10 holiday concerts this afternoon that will put him in touch with 20,000 more Nero lovers before its last jingle bells have fallen silent.

Nero has led the Pops since its founding in 1979, and his Broad Street encounter embodies the kind of relationship any arts group today would kill for.

Which makes this moment in time all the more interesting, since despite his balletic vigor and a nimble pianism (as likely to reference Tchaikovsky as Oscar Peterson), Nero, 73, clearly won’t stand atop his podium forever.

Not that the Pops is making any real succession plans. Things are too good. The Pops, which now operates under the organizational arm of the Philadelphia Orchestra Association, plays to 90 percent-of-capacity houses. It contributed $600,000 to the Philadelphia Orchestra’s budget in the last fiscal year, which helped the orchestra end the year in the black.

“Peter’s not going anywhere,” said Craig Hamilton, the Pops’ general manager. “Peter is the brand.”

It’s true literally as well as figuratively: Nero owns the name of the group. “There’s a licensing fee the Philadelphia Orchestra Association pays for use of the brand Peter Nero and the Philly Pops,” Hamilton says.

Some pops orchestras build seasons around repertoire – Broadway, big-band nostalgia acts, light classics such as Rhapsody in Blue – or lure audiences with bankable, big-name artists like Johnny Mathis.

The Philly Pops has programmed such elements. But the group – which was started by impresario Moe Septee – has built its constituency mainly on the star power of a thrice-married, Brooklyn-born, former child prodigy whose inability to separate music into neatly defined genres has won him love and prosperity.

Nero is the conductor who, in a single two-hour concert, programmed music from Saturday Night Fever and Carmen. And Alfie. And Beethoven’s Symphony No. 9.

“It was a test of musical brotherhood,” wrote one music critic of that 1980 concert. But “it seemed to work,” he concluded.

“I enjoy showing how the lines blur,” said Nero, who was born Bernard Nierow, but whose name was changed by his agent and recording label. “Rachmaninoff, to me, influenced every jazz pianist who came along.”

The charm of the presentation, the Nero touch, has a lot to do with making a success of unlikely repertoire bedfellows. Nero carries on with members of the audience. He contextualizes in a way that makes an audience that might not know classical music feel a warm hand bringing them along.

“Last year I did Brahms’ Academic Festival Overture, and the concept of this concert had nothing to do with Brahms or Academic or Festival. I gave them the background on it, that Brahms wrote it when he got roped into accepting an honorary degree. I joked with them that it was from Trenton State. And I told them the story about how he got back at them by using three drinking songs in it. I looked up the lyrics and it was pretty bawdy.”

His connection with audiences goes both ways. After a recent concert in Baltimore, about 200 fans lined up to greet Nero, Hamilton says.

“I don’t think there’s a better example of audience engagement in the arts right now,” he said. Museums, orchestras and theaters see their future less in mass marketing and more in establishing personal relationships with patrons. “Peter has been there for years,” Hamilton says.

Nero spends a tremendous amount of time talking to listeners, asking what they liked, learning who they are, getting inside their heads. At one concert, he could have told the audience the orchestra would be playing the “Dance of the Hours” from La Gioconda by Amilcare Ponchielli. But instead he told them it started with “Hello Muddah, Hello Faddah” and ended with the music from a toothpaste commercial airing at the time.

Lightbulbs went on.

In order to get classical works in the ears of his audiences, Nero doesn’t mind taking shortcuts that would make classical’s orthodox element (which is most of it) jump out of their skin. He not only does the Grieg Piano Concerto in one movement, he does a movement from a Rachmaninoff symphony with big cuts.

Then again, maybe it’s not the classical purists he needs to worry about.

“I did an arrangement that mixed the 1812 Overture and ‘Over the Rainbow.’ Somebody called and said, ‘How could you do that to “Over the Rainbow” ‘?”

Nero doesn’t kid himself that introducing classics to a pops audience will win subscribers for the Philadelphia Orchestra. It’s just about playing the music he likes, he says. “It has to be a combination of things you put in their laps and things that are a challenge, because if it’s not a challenge, they’re going to get bored.”

To Nero, all music is created equal, regardless of the genre. Absence of a qualitative hierarchy in music is a popular belief now, but Nero has always lived it. His recordings – starting in 1961 when RCA signed him to 24 albums over eight years – are a fascinating exercise in time travel.

On the album Love Songs for a Rainy Day, Nero is a romantic cocktail pianist. Peter Nero’s Greatest Hits is a heady flashback to the ’70s, with a theme from Summer of ’42 sporting swellegant strings, harp glissandi, a melancholy English horn, and eerie distant voices. The harpsichord-infused theme from Love Story has all the sad, tinny poignancy of a Lucite tabletop music box.

He can be Liberace, or George Shearing. Gamble and Huff, or Rodgers and Hart.

Nero has the credentials to be anything he wants. He studied at New York’s High School of Music and Art, and took lessons at Juilliard on Saturdays. He earned a B.A. at Brooklyn College – alma mater of both his Ukrainian Jewish father and his Jewish mother, whose parents emigrated from the island of Rhodes – but studied privately with esteemed piano pedagogues Abram Chasins and Chasins’ wife, Constance Keene.

Nero says his parents weren’t musical, but knew enough to buy him a good piano. “When I was 11, they bought me a used Steinway Model O. It was $1,100, which was a lot of money back then. It was the only time they borrowed money.”

He played the popular children’s talent shows of the 1950s – incubators for much of the entertainment industry’s talent for decades after – and came to the attention of Paul Whiteman, with whom he toured for several years. He had his own trio at the Tropicana in Las Vegas, returned to New York to play intermission piano at the Hickory House, and was hired by Jilly’s, the fabled 52d Street saloon that was a hangout for Frank Sinatra, Jackie Gleason and their circle. He spent two important years there developing his jazz chops with the encouragement of its colorful owner, Jilly Rizzo.

It was the deal with RCA that spread his sound far and wide. And then, with a move to Columbia Records, he scored big in the ’70s with a Summer of ’42 single, whose sales quickly reached $1 million.

Along the way, he was married three times. First to his childhood sweetheart; they had two children. Second to a flight attendant from Alabama. There was a bit of a cultural difference, he now concedes. His current wife is Rebecca Edie, a pianist for the Philly Pops. They met on a gig and have been together for 10 years.

Nero composes and arranges, in addition to still spending a lot of time conducting. The Philly Pops post involves considerable administrative time – auditioning talent, Googling around for arrangements, assembling programs that are finalized so last-minute there’s never a printed program.

When he doesn’t play the piano at Philly Pops concerts, he says, he gets letters. There’s something very personal about the way listeners come to love the style, the touch, the sensibilities of a particular pianist.

True, too, for Nero. At some point each year, you can find this two-time Grammy winner – who has worked with Sinatra, Mel Torme and Rod Stewart – playing to small crowds in Florida retirement homes. Financially, he clearly doesn’t need that.

He does it, he says, because he misses the piano.

Ray Charles understood Nero’s place in the piano pantheon. Musing about his favorite pianists in Keyboard Magazine, he said: “Art Tatum could play anything he wanted to. . . . Of course, Oscar [Peterson] is my man. . . . I probably feel closest to Hank Jones after Oscar . . .

“And Peter Nero plays his buns off!”

(This article appeared on Philly.com Sunday, December 9, 2007)